Income tax is a direct tax on the income you earn. It’s one of the main ways governments fund public services like roads, schools, and hospitals. If you’re earning above a certain amount in India, you are required by law to pay income tax. Understanding how income tax works is important – it helps you plan your finances and ensure you’re paying the right amount and not too much or too little.

What Are Income Tax Slabs?

India follows a slab system for income tax, which means income is taxed in brackets or “slabs.” Simply put, the tax rate increases as your income increases, but only on the portion of income within each bracket. This ensures fairness – higher earners pay a higher percentage on their extra income, while those with lower income pay at lower rates.

Read Also: Money 101: Beginner’s Guide To Financial Literacy

The New Tax Regime Slabs for FY 2024–25 (AY 2025–26)

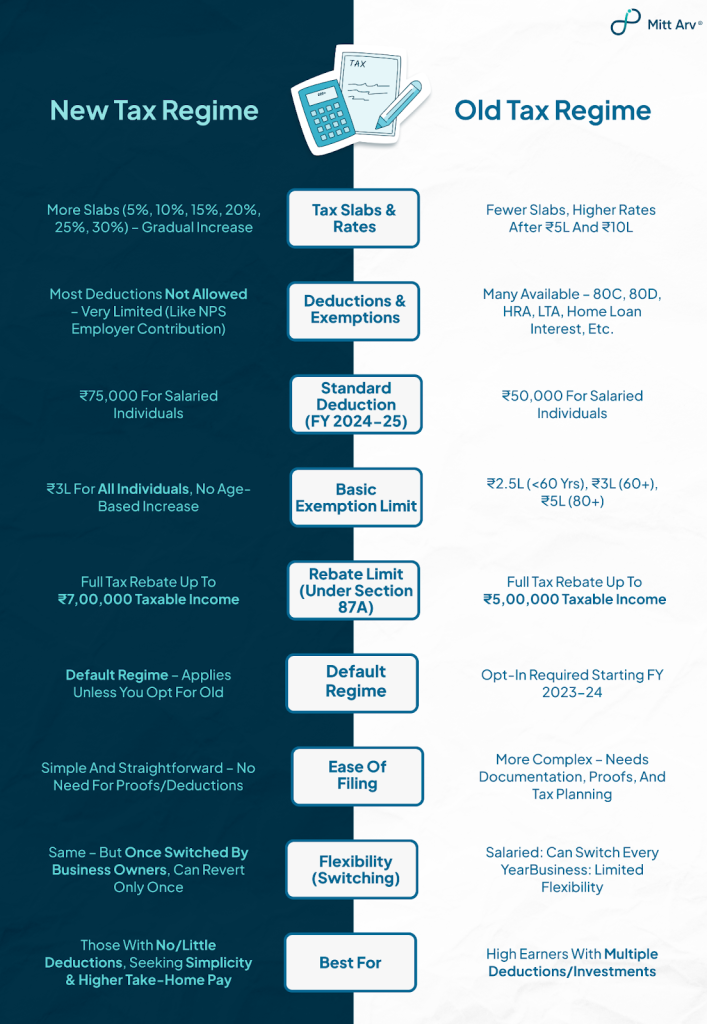

India currently has two parallel tax systems for individuals: the new tax regime and the old tax regime. The new tax regime, introduced in 2020, is now the default tax system for FY 2024–25. This regime offers lower tax rates spread across more slabs, but does not allow most of the common deductions or exemptions, like those for investments or house rent that were available in the old system. The idea is to simplify taxation with lower rates and a straightforward structure.

Income Tax Slabs under the New Regime (FY 2024–25):

| Annual Taxable Income Range (₹) | Tax Rate (New Regime) |

| Up to ₹3,00,000 | Nil (0%) |

| ₹3,00,001 to ₹7,00,000 | 5% of income in this range |

| ₹7,00,001 to ₹10,00,000 | 10% of income in this range |

| ₹10,00,001 to ₹12,00,000 | 15% of income in this range |

| ₹12,00,001 to ₹15,00,000 | 20% of income in this range |

| Above ₹15,00,000 | 30% of income beyond ₹15,00,000 |

Important features of the New Regime:

- No Tax up to ₹7 lakh: Even though the slab rates start at 5% for income beyond ₹3 lakh, the government provides a full tax rebate under Section 87A of the Income Tax Act, 1961, for taxable incomes up to ₹7 lakh. This means if your total taxable income (after any eligible deductions) is ₹7,00,000 or less, you pay zero tax in the new regime. Essentially, the rebate wipes out your tax liability up to that income level.

| For instance: If you earn ₹7 lakh, the calculated tax would be 5% of ₹4 lakh = ₹20,000, but a rebate of ₹20,000 will be applied, making your net tax ₹0. |

- Basic Exemption Limit: Under this regime, the first ₹3,00,000 of your income is not taxed at all. This exemption is higher than the old regime’s ₹2.5 lakh for non-senior taxpayers. It means everyone gets a ₹3 lakh tax-free cushion under the new system.

- Standard Deduction for Salaried/Pensioners: Under the new regime in FY 2024–25, salaried individuals and pensioners can claim a standard deduction of ₹75,000 from their salary income. This is an increase from the ₹50,000 standard deduction, which was introduced earlier, a change made to make the new regime more attractive to salary earners.

| For example: If your annual salary is ₹7,75,000, you can subtract ₹75,000 and only ₹7,00,000 would be counted as taxable income (and as we saw, ₹7 lakh would then be entirely tax-free due to the rebate!). |

- No Common Deductions/Exemptions: Aside from the standard deduction and a few very specific deductions like the employer’s NPS contribution under Section 80CCD(2) of the Income Tax Act, 1961, most tax breaks are not allowed in the new regime. This means popular deductions/exemptions like Section 80C (investments up to ₹1.5 lakh), 80D (medical insurance premium), HRA (House Rent Allowance), home loan interest, etc., cannot be claimed if you opt for the new regime. The new regime is essentially “what you see is what you get”; you pay tax on your gross taxable income as per the slabs without adjusting it down with multiple deductions.

- Simplified Compliance: Many find the new regime simpler because you don’t need to track and declare various investments or expenses to claim deductions. It’s especially convenient for those who don’t have many tax-saving investments or those who find the paperwork burdensome. The filing process can be more straightforward since you’re not itemizing deductions.

Read Also: Financial Literacy for Students

The Old Tax Regime Slabs for FY 2024–25

The old tax regime is the traditional tax system that was in place before the new regime came into effect. It is now optional. Taxpayers can choose to stick with the old regime when filing taxes if they find it beneficial. The old regime has higher tax rates for certain income ranges but allows various tax deductions and exemptions, which can reduce your taxable income. This means you can lower your tax by investing or spending in specified ways, like contributing to provident funds, buying insurance, paying tuition fees, etc., under sections like 80C, 80D, and by claiming allowances like HRA.

Under the old regime for FY 2024–25, the tax slabs and rates for individuals below 60 years of age are:

| Annual Taxable Income Range (₹) | Tax Rate (Old Regime) |

| Up to ₹3,00,000 | Nil (0%) |

| ₹0 to ₹2,50,000 | Nil (0% tax) |

| ₹2,50,001 to ₹5,00,000 | 5% of income in this range |

| ₹5,00,001 to ₹10,00,000 | 20% of income in this range |

| Above ₹10,00,000 | 30% of income beyond ₹10,00,000 |

Special Exemptions for Seniors in Old Regime: The old regime provides a slightly higher basic tax exemption for senior citizens: if you are 60 years or older, you don’t pay tax until ₹3,00,000 of income; if you are 80 years or older (super senior), you have no tax up to ₹5,00,000. This is a benefit, recognizing that senior citizens might have limited income or higher expenses. In the new regime, however, the basic exemption is a flat ₹3 lakh for everyone regardless of age.

Rebate under Section 87A: Just like the new regime, the old regime also offers a rebate for low incomes, but it’s a bit less generous. If your taxable income is up to ₹5,00,000, you are eligible for a 100% tax rebate on your tax liability (up to a maximum of ₹12,500). In effect, this means you pay zero tax on income up to ₹5 lakh in the old regime as well, provided your income after deductions is ₹5 lakh or below.

| For example: If your taxable income comes to ₹4.8 lakh, the tax would be calculated (5% of ₹2.3 lakh, which is ₹11,500), but then a rebate of ₹11,500 would nullify it. However, if your taxable income is even slightly above ₹5 lakh (say ₹5.1 lakh), you don’t get any rebate at all and would have to pay the full tax as per slabs on the entire amount. |

So, staying within that ₹5 lakh threshold can be key for zero tax under the old system.

| Remember: Under the new regime, this threshold is higher at ₹7 lakh. |

Deductions and Exemptions: The old regime’s biggest advantage is the ability to reduce your taxable income through various deductions and exemptions. Some common ones include:

- Standard Deduction of ₹50,000: Salaried individuals (and pensioners) get an automatic flat deduction of ₹50,000 from their income. This is meant to cover work-related expenses without needing bills. (It’s lower than the ₹75,000 standard deduction now offered in the new regime for FY 24–25.)

- Section 80C deductions (up to ₹1.5 lakh): This includes popular tax-saving investments and expenses like Employees’ Provident Fund (EPF), Public Provident Fund (PPF), life insurance premiums, ELSS mutual funds, National Savings Certificates, children’s tuition fees, principal on home loan, etc. You can claim up to ₹1,50,000 of such investments to reduce your taxable income.

- Section 80D (Medical Insurance): You can deduct premiums paid for health insurance (for yourself, family, and parents), usually up to ₹25,000 for self/family and additional ₹25,000 for parents (higher if parents are senior citizens).

- House Rent Allowance (HRA): Salaried individuals who receive HRA and pay rent can claim a deduction for rent under certain conditions. This can be a significant exemption if you live in rented accommodation.

- Home Loan Interest (Section 24): If you have a home loan, up to ₹2,00,000 of the interest paid in a year can be deducted from your income for a self-occupied house under the old regime.

- Other deductions: There are others like Section 80TTA for deduction on savings account interest up to ₹10,000, Section 80EEA for additional home loan interest for first-time homebuyers, 80G for charitable donations, etc.

These deductions can substantially bring down your taxable income if you have made those investments or payments.

| For example: A salaried person earning ₹10 lakh could invest ₹1.5 lakh in 80C options, pay ₹20,000 in health insurance, claim ₹50,000 standard deduction, etc., and easily bring taxable income down by a few lakhs, thereby reducing tax. This flexibility is why many taxpayers, especially those who are disciplined in tax-saving investments, still consider the old regime. |

The old regime rewards you for saving and investing by giving tax breaks, whereas the new regime gives a lower rate upfront without asking you to invest in specific instruments.

New vs Old Tax Regime

Read Also: Credit Score 101: What It Is, Why It Matters, and How to Boost It?

How to Choose Tax Regime in India

Choosing the right tax regime can save you money. Here are some simple steps and tips to help you decide which regime is better for you:

- List out your possible deductions/exemptions

Start by enumerating all the tax-saving investments or expenses you have for the year if you were to use the old regime. This includes your PF contributions, insurance premiums, investments under 80C, any eligible house rent for HRA, education loan interest, home loan interest, etc. Calculate the total of these deductions.

| For example: “I have ₹1,00,000 in EPF, plan to invest ₹50,000 in PPF, pay ₹20,000 in health insurance, and have ₹1,80,000 of home loan interest.” Summing these up (while respecting individual section limits) will give you an idea of how much of your income you can shield from tax under the old regime. |

- Calculate tax under both regimes

You don’t have to do this manually – you can use an online income tax calculator (many are available for free, including on the Income Tax Department website) to input your income and deductions. But conceptually, do this:

- Under the old regime: Subtract all the deductions from your gross income (and standard deduction). This gives your net taxable income for the old regime. Now apply the old slabs to compute tax. (Again, an online calculator or a simple spreadsheet can do this quickly.)

- Under new regime: Ignore all those deductions except the standard deduction (₹75k if salaried). Apply the new slabs on the remaining income. Compute the tax.

- Compare the tax amount

Compare the tax amount you get under each whichever is lower – that regime is financially better for you for that year. For instance, if the old regime tax comes to ₹50k and the new regime comes to ₹70k, stick with the old regime since you saved ₹20k by using deductions. If a new regime comes out lower, go for the new regime.

- Consider your ability to invest or spend on those deductions

It’s not just about the math of tax, also think practically. Could using the old regime be forcing you to lock money in certain investments that you wouldn’t otherwise do? If you weren’t going to invest that ₹1.5 lakh in 80C instruments anyway, but you’re only doing it to save tax, is it affordable for you?

Sometimes people choose new regime because they prefer having liquidity (cash in hand) rather than putting money into say a 5-year locked tax-saver deposit just to save some tax. If you find it hard to save/invest money, you might lean towards the new regime which doesn’t require it.

- Income Level Matters

Broadly, for lower incomes (up to ₹7L taxable), the new regime is very attractive because of zero tax up to ₹7L. For middle incomes (say ₹7L–₹15L), the decision depends on deductions: the new regime often does well unless you have pretty large deductions (several lakhs). For higher incomes (above ₹15L), you might find that if you can maximize many deductions (like full 80C, 80D, HRA, home loan interest, etc.), the old regime could reduce your tax significantly, but you need to crunch the numbers.

| You should know: Recent data suggests that even up to ₹12-13L, new regime can compete strongly with old regime even if old is leveraged, due to the new regime’s lower rates and higher rebate. So the tipping point has shifted upward in favor of the new regime for many. But at very high incomes, since the slab rate (30%) eventually is the same in both, it’s all about how many rupees you can deduct in old regime to avoid that 30% tax. If those rupees are more than enough, old may win; if not, new could still hold up. |

- Simplicity vs. Involvement

Ask yourself how much you want to engage in tax planning. If you enjoy/plan your finances in detail and don’t mind the extra steps, you might not mind the old regime’s requirements. If you’d rather keep things straightforward, the new regime’s simplicity is a big plus.

For many salaried individuals who just have Form-16 and not much else, opting for the new regime means they don’t have to think about tax much beyond checking the correct TDS. But if you derive satisfaction from optimizing your tax or if you have family investments that align with old regime benefits, then that route could be worthwhile.

Read Also: 50/30/20 Budgeting Strategy

- Revisit Each Year

Remember, if you’re not having business income, you can switch regimes every year. So you might choose the old regime one year (say you paid a lot of tuition fees or something and want to claim it) and maybe next year if you don’t have similar expenses, you might flip to the new regime. It’s not a permanent choice for salaried folks; treat it as a yearly decision. Evaluate your situation each financial year or at least at the time of filing your return, and pick the regime that suits that year’s numbers.

| Tip: Many experts suggest a rough rule: If your total eligible deductions are very low (or nil), the new regime is likely better. If your eligible deductions are very high, the old regime might save you more. There are break-even estimates; for example, one guideline (for middle incomes) is that if your deductions are less than about ₹3 lakh, the new regime could be better, whereas if you can claim more than that, the old regime might start making more sense. But these are generalities – actual outcomes can vary with income levels and specific scenarios. The best approach is to compute both ways. |

FAQs for Beginners

Q1. What exactly does FY 2024–25 mean? How is it different from AY 2025–26?

A: FY stands for Financial Year – it’s the year in which you earn the income. FY 2024–25 means income earned between April 1, 2024 and March 31, 2025. AY stands for Assessment Year, which is the year in which you file your tax return and the income is assessed, it’s basically the year after the FY.

In simple terms, FY is the period you earn money, and AY is the period you file the return for that money.

Q2. Is the new tax regime mandatory? What if I want to stick to the old regime?

A: The new regime is not mandatory – it’s optional, but it is the default. This means if you do nothing, you’ll be considered under the new regime by default (especially for tax deducted at source on salary, etc.). If you prefer the old regime (because you have deductions to claim), you absolutely can opt for it.

Q3. Can I switch between the old and new tax regime every year?

A: If you are a salaried individual or pensioner (i.e., you do not have income from a business/profession), yes, you can decide each financial year which regime to opt for. There’s no restriction – you can pick old this year, new next year, and so on, based on what is favorable.

However, if you have business or professional income and you opt for the new regime, switching back is not easy, the law currently allows a one-time switch back for those with business income.

Q4. What if I choose the wrong regime and realize later I’d have paid less tax in the other?

A: If this realization happens before the tax filing deadline (typically July 31 after the FY), you can simply choose the other regime when filing your return, and adjust things.

If you already filed the return and then realize you made the wrong choice, you can file a revised return (before the deadline for revisions) and correct the regime selection. However, once all deadlines pass, you’re generally locked in for that year. You cannot arbitrarily change the regime after the assessment is complete or try to switch in the middle of the year for the same year’s income.